Picture This

If you can’t you may have Aphantasia!

From the time I was little, and even into my young adulthood, when I was told to "picture" something in my mind, I thought it was metaphorical. To me, this meant thinking of an object, focusing my thoughts on it, and trying to conjure any knowledge I might have about the object I was told to picture. Then, somewhere in my mid-20s, I learned something ground-breaking. Picturing something in your mind was not intended to be a metaphor. Most people can literally see images in their minds. This led me down a rabbit hole, researching the relatively little information that exists on a condition I now discovered I had. Aphantasia. Aphantasia is the inability to form mental images.

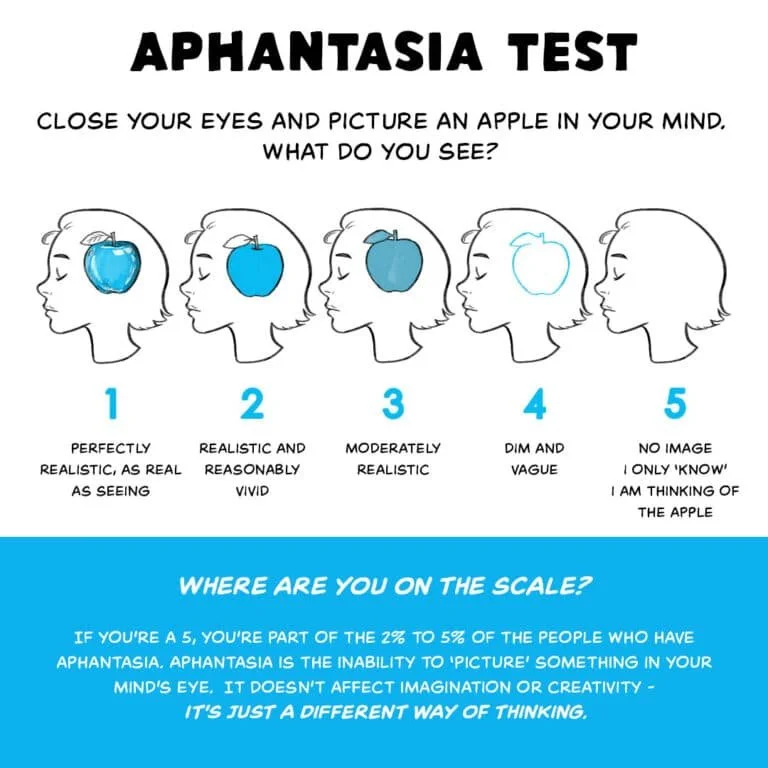

Discovering aphantasia is probably as ground-breaking for people who don't have it as it is for those of us who do. If I don't see images in my mind, a logical question you might have is, "What goes on in there?" The answer is nothing and everything, but let's take a look at aphantasia before we dive too deep into my experience. Like many things, aphantasia is a spectrum. It's easily conceptualized with a simple test. Close your eyes, focus hard, and imagine an apple. Using the scale below, how vivid is the image you see?

https://creativerevolution.io/aphantasia-a-blind-minds-eye/

I am 4.5(1) the vast majority of the time. Occasionally, I can conjure a blurry image that might qualify as a 4, but it usually blips out after a second or two. After seeing this scale, things started to click for me. That simple test may teach you about yourself, too. Maybe you have aphantasia and didn't know it until reading this. It is estimated that between 2 and 5% of people have aphantasia. However, that range is very speculative due to how little research has been done. That being said, I'm still probably in the vast minority. But why is it worth talking about? It can't be that significant if I lived with this for most of my life and didn't even realize it. Well, learning about it has led me to some insights about how my brain works and helped me understand myself better. I want to bring you into my world and show you what it's like before I get to the insights, though.

If you ask me to picture my house, I can't do it. I should have a clear mental image of it, but I don't. What I "see" in my mind is almost entirely blank unless I physically look at it. Now, that doesn't mean I couldn't describe it to you. I can list off facts. I live in a blue Cape Cod-style house with white trim and a yellow front door. When looking at the house, the large picture window on the right is the living room, and the smaller windows to the left are a bedroom. There's a concrete stoop leading to the door. The front yard is mostly grass with a landscaping strip around the house. In front of the living room are 3 bushes of various sizes, the smallest toward the side and the largest toward the center. In front of the bedroom is another large bush near the center of the house and a cedar tree toward the side. Without too much effort, I probably just gave you a good mental image of my house, one that I don't have myself.

That process becomes much more difficult for me when the characteristics of what I'm trying to describe are more subjective. If you ask me to describe my wife, the mental picture I can give you is much less clear. People's physical traits, such as the shape of a face or somebody's demeanor, aren't "facts" I can remember. Even though I spend hours nearly every day with my wife, my mental picture of her still hovers around a 4 on the scale we used above, basically a vague outline of her. This is equally true for people I've known much longer, like my parents and siblings.

Clearly, my mental processes are not visual. So, back to the question of what goes on in my mind. When I think, my thoughts align with an object's Platonic ideals. To draw back to the previous example, when I'm "picturing" a house, I'm not thinking about my house or even an imaginary house like most people probably do. Instead, I'm thinking about the idea of a house, its essence, no visuals necessary.

So what? Why does it matter? Well, I've come to find that it explains a lot about how I think and has highlighted some strengths I have. I think more abstractly. As I mentioned in my last post, I love philosophy. Most people don't because it's too abstract for them to grasp. On the other hand, I was fluent in that abstract language. Philosophy has been relatively easy for me to understand, analyze, and translate some of its principles into my life. I've used it to shape and reshape myself into the person I aspire to be. Benefit. I've also realized that my thought processes can be abstract and difficult to follow. When I speak, I have a tendency to trail off mid-sentence and then continue on a seemingly unrelated train of thought. When I do this, it's often because I have trouble finding the words I need to express my thoughts clearly. Back to Plato, I'm the fire in the cave trying to convey an ideal, which is impossible to do without corrupting it. So, I stop talking, not wanting to corrupt the ideal, but I assume you understand what I mean. You can fill in the gap, and we can continue without interruption. I've found that people often can't fill in the gaps I leave them and just follow along on my seeming tangents. If I'm not conscious of the fact that we are thinking differently, communication between me and others can get mixed up. Downside.

I'm also a high-level thinker. I recently talked with a coworker about some issues on a design project. We had a retrofit design and proposed shifting the new curb ramp about a foot from the existing ramp. She didn't see that the change effectively meant we would have to reassess the geometry of an entire intersection. Once I explained the chain reactions, she understood how the small decision made an outsized impact, but she admitted that she wouldn't have come to that conclusion if it hadn't been pointed out. She was so focused on the ramp that the intersection as a whole didn't enter her mind. So I can see problems, or solutions for that matter, where others can't. Benefit. I can also get stuck in analysis paralysis. I dig myself into a hole by refusing to just start somewhere, anywhere, until I see the whole picture clearly. The puzzle needs to be clear before I start putting the pieces together, and sometimes, that means the puzzle never gets started. Downside.

It also explains some trivial differences between me and others. For example, many people hate seeing a movie before reading a book. They say the on-screen portrayals ruin their ability to form an independent mental picture of the characters, the setting, etc. On the other hand, I find it helpful to have seen a movie first because then I have some basis for what the characters look like. Harry Potter looks like Daniel Radcliffe, got it. I still can't "picture" it, but at least I have a frame of reference. Once, my wife and I talked about a book she was reading. She started describing a fantasy world she had built in her mind with the use of the narrative in the book, and it fascinated me. I also think aphantasia explains my lack of dreams. If I'm not good at forming mental pictures in my conscious life, it seems reasonable to assume I'm not good at it in my unconscious sleep, either.

Are there ever times when I have clear mental images? There are a few very specific instances where I can conjure mental images. The most common is what I call purple haze. Frequently, when I am meditating or in a relaxed state with my eyes closed, like before bed or in a sensory deprivation tank, I "see" what is best described as purple smoke. If I try to see it, it quickly goes away, but if I just let it come to me, it usually does. I have no control over it, and it's always purple haze. But it's there. Similarly, if I am in the flow state, miles deep into an easy-paced long run, for example, I can sometimes conjure up rough mental images of whatever thoughts are going through my mind.

I can also manipulate the object in my mind if I am deeply focused and looking at the object, a combination of mental and visual imagery. This comes in handy often at work. Plan sets are a 2D representation of a 3D object. I can focus on that 2D image, make it 3D in my mind, and spin it around to assess all aspects of it, pinpointing issues or potential clashes with other elements. I cannot do this without looking at a representative object, though.

Unfortunately for me, the most vivid mental images I can conjure are during sleep paralysis. The "sleep paralysis demon," if you know you know, is incredibly vivid. I may as well be seeing that in real life. Thankfully, while this is my most common dream, my dreams are rare, as I mentioned above. (I will probably dive into my weird relationship with dreams some other time.)

While there are abilities aphantasia has kept from me, seeing a picture of my loved ones whenever I want would be nice; I don't think I would get rid of it if given the choice. If every nightmare I had was as vivid as the sleep paralysis demon, I would probably sleep worse than I already do. If there was a constant movie playing in my head whenever I was trying to focus on something, I'd get distracted, and my ability to conceptualize and further dive into a topic would be stunted. Life without aphantasia sounds overwhelming.

Realizing I had aphantasia didn’t change my life overnight. But it gave me a more nuanced understanding of how I think and how others do, too. That awareness helps me navigate life with more clarity. You may not have aphantasia, but you undoubtedly also process the world with your own nuance and perspective. Recognizing and embracing those differences is how we enrich not only our own lives but the world around us.

(1) Technically, this means I have hypophantasia, not aphantasia, but I don't think the distinction is too important at the moment.